Cyber Security

Kimwolf Botnet Swamps Anonymity Network I2P – Krebs on Security

For the past week, the massive “Internet of Things” (IoT) botnet known as Kimwolf has been disrupting The Invisible Internet Project (I2P), a decentralized, encrypted communications network designed to anonymize and secure online communications. I2P users started reporting disruptions in the network around the same time the Kimwolf botmasters began relying on it to evade takedown attempts against the botnet’s control servers.

Kimwolf is a botnet that surfaced in late 2025 and quickly infected millions of systems, turning poorly secured IoT devices like TV streaming boxes, digital picture frames and routers into relays for malicious traffic and abnormally large distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks.

I2P is a decentralized, privacy-focused network that allows people to communicate and share information anonymously.

“It works by routing data through multiple encrypted layers across volunteer-operated nodes, hiding both the sender’s and receiver’s locations,” the I2P website explains. “The result is a secure, censorship-resistant network designed for private websites, messaging, and data sharing.”

On February 3, I2P users began complaining on the organization’s GitHub page about tens of thousands of routers suddenly overwhelming the network, preventing existing users from communicating with legitimate nodes. Users reported a rapidly increasing number of new routers joining the network that were unable to transmit data, and that the mass influx of new systems had overwhelmed the network to the point where users could no longer connect.

I2P users complaining about service disruptions from a rapidly increasing number of routers suddenly swamping the network.

When one I2P user asked whether the network was under attack, another user replied, “Looks like it. My physical router freezes when the number of connections exceeds 60,000.”

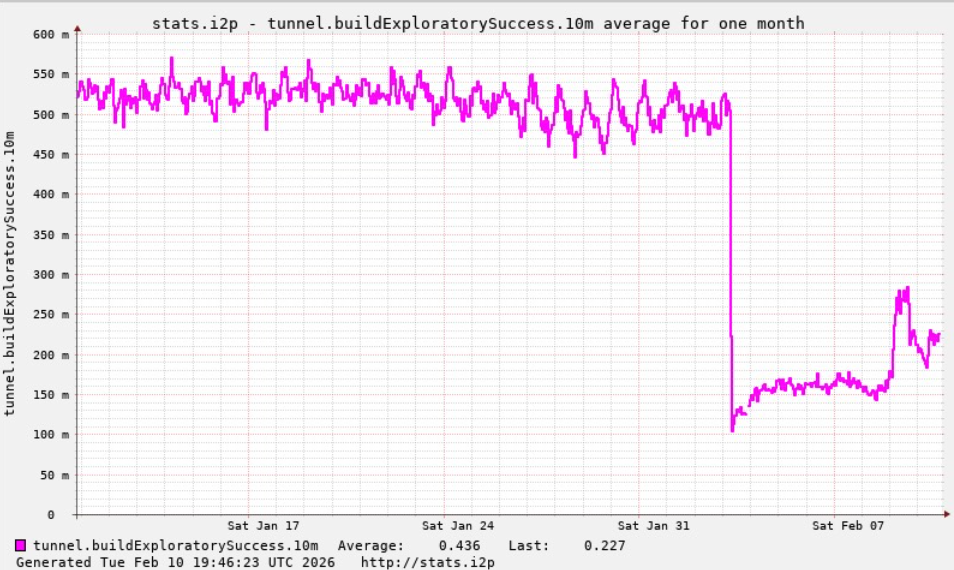

A graph shared by I2P developers showing a marked drop in successful connections on the I2P network around the time the Kimwolf botnet started trying to use the network for fallback communications.

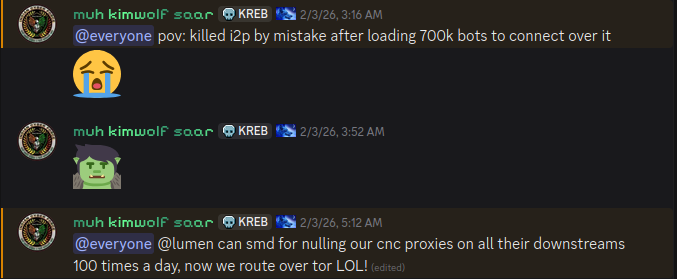

The same day that I2P users began noticing the outages, the individuals in control of Kimwolf posted to their Discord channel that they had accidentally disrupted I2P after attempting to join 700,000 Kimwolf-infected bots as nodes on the network.

The Kimwolf botmaster openly discusses what they are doing with the botnet in a Discord channel with my name on it.

Although Kimwolf is known as a potent weapon for launching DDoS attacks, the outages caused this week by some portion of the botnet attempting to join I2P are what’s known as a “Sybil attack,” a threat in peer-to-peer networks where a single entity can disrupt the system by creating, controlling, and operating a large number of fake, pseudonymous identities.

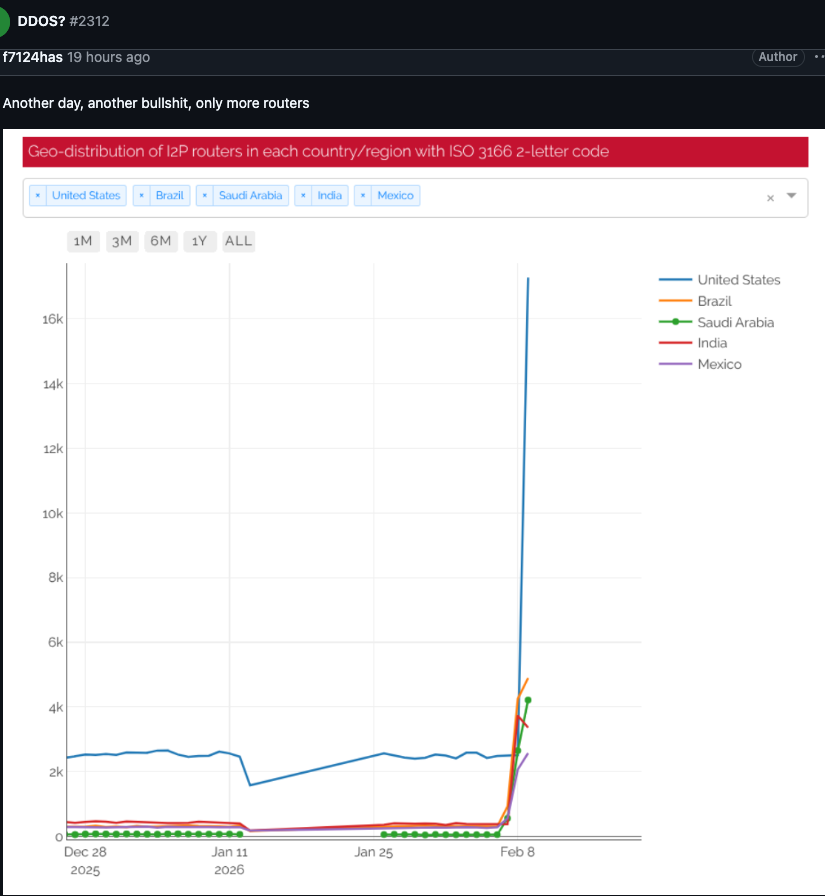

Indeed, the number of Kimwolf-infected routers that tried to join I2P this past week was many times the network’s normal size. I2P’s Wikipedia page says the network consists of roughly 55,000 computers distributed throughout the world, with each participant acting as both a router (to relay traffic) and a client.

However, Lance James, founder of the New York City based cybersecurity consultancy Unit 221B and the original founder of I2P, told KrebsOnSecurity the entire I2P network now consists of between 15,000 and 20,000 devices on any given day.

An I2P user posted this graph on Feb. 10, showing tens of thousands of routers — mostly from the United States — suddenly attempting to join the network.

Benjamin Brundage is founder of Synthient, a startup that tracks proxy services and was the first to document Kimwolf’s unique spreading techniques. Brundage said the Kimwolf operator(s) have been trying to build a command and control network that can’t easily be taken down by security companies and network operators that are working together to combat the spread of the botnet.

Brundage said the people in control of Kimwolf have been experimenting with using I2P and a similar anonymity network — Tor — as a backup command and control network, although there have been no reports of widespread disruptions in the Tor network recently.

“I don’t think their goal is to take I2P down,” he said. “It’s more they’re looking for an alternative to keep the botnet stable in the face of takedown attempts.”

The Kimwolf botnet created challenges for Cloudflare late last year when it began instructing millions of infected devices to use Cloudflare’s domain name system (DNS) settings, causing control domains associated with Kimwolf to repeatedly usurp Amazon, Apple, Google and Microsoft in Cloudflare’s public ranking of the most frequently requested websites.

James said the I2P network is still operating at about half of its normal capacity, and that a new release is rolling out which should bring some stability improvements over the next week for users.

Meanwhile, Brundage said the good news is Kimwolf’s overlords appear to have quite recently alienated some of their more competent developers and operators, leading to a rookie mistake this past week that caused the botnet’s overall numbers to drop by more than 600,000 infected systems.

“It seems like they’re just testing stuff, like running experiments in production,” he said. “But the botnet’s numbers are dropping significantly now, and they don’t seem to know what they’re doing.”

Cyber Security

Patch Tuesday, February 2026 Edition – Krebs on Security

Microsoft today released updates to fix more than 50 security holes in its Windows operating systems and other software, including patches for a whopping six “zero-day” vulnerabilities that attackers are already exploiting in the wild.

Zero-day #1 this month is CVE-2026-21510, a security feature bypass vulnerability in Windows Shell wherein a single click on a malicious link can quietly bypass Windows protections and run attacker-controlled content without warning or consent dialogs. CVE-2026-21510 affects all currently supported versions of Windows.

The zero-day flaw CVE-2026-21513 is a security bypass bug targeting MSHTML, the proprietary engine of the default Web browser in Windows. CVE-2026-21514 is a related security feature bypass in Microsoft Word.

The zero-day CVE-2026-21533 allows local attackers to elevate their user privileges to “SYSTEM” level access in Windows Remote Desktop Services. CVE-2026-21519 is a zero-day elevation of privilege flaw in the Desktop Window Manager (DWM), a key component of Windows that organizes windows on a user’s screen. Microsoft fixed a different zero-day in DWM just last month.

The sixth zero-day is CVE-2026-21525, a potentially disruptive denial-of-service vulnerability in the Windows Remote Access Connection Manager, the service responsible for maintaining VPN connections to corporate networks.

Chris Goettl at Ivanti reminds us Microsoft has issued several out-of-band security updates since January’s Patch Tuesday. On January 17, Microsoft pushed a fix that resolved a credential prompt failure when attempting remote desktop or remote application connections. On January 26, Microsoft patched a zero-day security feature bypass vulnerability (CVE-2026-21509) in Microsoft Office.

Kev Breen at Immersive notes that this month’s Patch Tuesday includes several fixes for remote code execution vulnerabilities affecting GitHub Copilot and multiple integrated development environments (IDEs), including VS Code, Visual Studio, and JetBrains products. The relevant CVEs are CVE-2026-21516, CVE-2026-21523, and CVE-2026-21256.

Breen said the AI vulnerabilities Microsoft patched this month stem from a command injection flaw that can be triggered through prompt injection, or tricking the AI agent into doing something it shouldn’t — like executing malicious code or commands.

“Developers are high-value targets for threat actors, as they often have access to sensitive data such as API keys and secrets that function as keys to critical infrastructure, including privileged AWS or Azure API keys,” Breen said. “When organizations enable developers and automation pipelines to use LLMs and agentic AI, a malicious prompt can have significant impact. This does not mean organizations should stop using AI. It does mean developers should understand the risks, teams should clearly identify which systems and workflows have access to AI agents, and least-privilege principles should be applied to limit the blast radius if developer secrets are compromised.”

The SANS Internet Storm Center has a clickable breakdown of each individual fix this month from Microsoft, indexed by severity and CVSS score. Enterprise Windows admins involved in testing patches before rolling them out should keep an eye on askwoody.com, which often has the skinny on wonky updates. Please don’t neglect to back up your data if it has been a while since you’ve done that, and feel free to sound off in the comments if you experience problems installing any of these fixes.

Cyber Security

Please Don’t Feed the Scattered Lapsus Shiny Hunters – Krebs on Security

A prolific data ransom gang that calls itself Scattered Lapsus Shiny Hunters (SLSH) has a distinctive playbook when it seeks to extort payment from victim firms: Harassing, threatening and even swatting executives and their families, all while notifying journalists and regulators about the extent of the intrusion. Some victims reportedly are paying — perhaps as much to contain the stolen data as to stop the escalating personal attacks. But a top SLSH expert warns that engaging at all beyond a “We’re not paying” response only encourages further harassment, noting that the group’s fractious and unreliable history means the only winning move is not to pay.

Image: Shutterstock.com, @Mungujakisa

Unlike traditional, highly regimented Russia-based ransomware affiliate groups, SLSH is an unruly and somewhat fluid English-language extortion gang that appears uninterested in building a reputation of consistent behavior whereby victims might have some measure of confidence that the criminals will keep their word if paid.

That’s according to Allison Nixon, director of research at the New York City based security consultancy Unit 221. Nixon has been closely tracking the criminal group and individual members as they bounce between various Telegram channels used to extort and harass victims, and she said SLSH differs from traditional data ransom groups in other important ways that argue against trusting them to do anything they say they’ll do — such as destroying stolen data.

Like SLSH, many traditional Russian ransomware groups have employed high-pressure tactics to force payment in exchange for a decryption key and/or a promise to delete stolen data, such as publishing a dark web shaming blog with samples of stolen data next to a countdown clock, or notifying journalists and board members of the victim company. But Nixon said the extortion from SLSH quickly escalates way beyond that — to threats of physical violence against executives and their families, DDoS attacks on the victim’s website, and repeated email-flooding campaigns.

SLSH is known for breaking into companies by phishing employees over the phone, and using the purloined access to steal sensitive internal data. In a January 30 blog post, Google’s security forensics firm Mandiant said SLSH’s most recent extortion attacks stem from incidents spanning early to mid-January 2026, when SLSH members pretended to be IT staff and called employees at targeted victim organizations claiming that the company was updating MFA settings.

“The threat actor directed the employees to victim-branded credential harvesting sites to capture their SSO credentials and MFA codes, and then registered their own device for MFA,” the blog post explained.

Victims often first learn of the breach when their brand name is uttered on whatever ephemeral new public Telegram group chat SLSH is using to threaten, extort and harass their prey. According to Nixon, the coordinated harassment on the SLSH Telegram channels is part of a well-orchestrated strategy to overwhelm the victim organization by manufacturing humiliation that pushes them over the threshold to pay.

Nixon said multiple executives at targeted organizations have been subject to “swatting” attacks, wherein SLSH communicated a phony bomb threat or hostage situation at the target’s address in the hopes of eliciting a heavily armed police response at their home or place of work.

“A big part of what they’re doing to victims is the psychological aspect of it, like harassing executives’ kids and threatening the board of the company,” Nixon told KrebsOnSecurity. “And while these victims are getting extortion demands, they’re simultaneously getting outreach from media outlets saying, ‘Hey, do you have any comments on the bad things we’re going to write about you.”

Nixon argues that no one should negotiate with SLSH because the group has demonstrated a willingness to extort victims based on promises that it has no intention to keep. Nixon points out that all of SLSH’s known members hail from The Com, shorthand for a constellation of cybercrime-focused Discord and Telegram communities which serve as a kind of distributed social network that facilitates instant collaboration.

Nixon said Com-based extortion groups tend to instigate feuds and drama between group members, leading to lying, betrayals, credibility destroying behavior, backstabbing, and sabotaging each other.

“With this type of ongoing dysfunction, often compounding by substance abuse, these threat actors often aren’t able to act with the core goal in mind of completing a successful, strategic ransom operation,” Nixon said. “They continually lose control with outbursts that put their strategy and operational security at risk, which severely limits their ability to build a professional, scalable, and sophisticated criminal organization network for continued successful ransoms – unlike other, more tenured and professional criminal organizations focused on ransomware alone.”

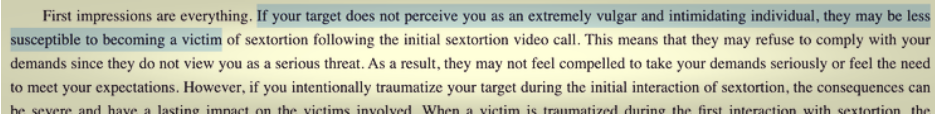

Intrusions from established ransomware groups typically center around encryption/decryption malware that mostly stays on the affected machine. In contrast, Nixon said, ransom from a Com group is often structured the same as violent sextortion schemes against minors, wherein members of The Com will steal damaging information, threaten to release it, and “promise” to delete it if the victim complies without any guarantee or technical proof point that they will keep their word. She writes:

The SLSH group steals a significant amount of corporate data, and on the day of issuing the ransom notification, they line up a number of harassment attacks to be delivered simultaneously with the ransom. This can include swatting, DDOS, email/SMS/call floods, negative PR, complaints sent to authority figures in and above the company, and so on. Then, during the negotiation process, they lay on the pressure with more harassment- never allowing too much time to pass before a new harassment attack.

What they negotiate for is the promise to not leak the data if you pay the ransom. This promise places a lot of trust in the extorter, because they cannot prove they deleted the data, and we believe they don’t intend to delete the data. Paying provides them vital information about the value of the stolen dataset which we believe will be useful for fraud operations after this wave is complete.

A key component of SLSH’s efforts to convince victims to pay, Nixon said, involves manipulating the media into hyping the threat posed by this group. This approach also borrows a page from the playbook of sextortion attacks, she said, which encourages predators to keep targets continuously engaged and worrying about the consequences of non-compliance.

“On days where SLSH had no substantial criminal ‘win’ to announce, they focused on announcing death threats and harassment to keep law enforcement, journalists, and cybercrime industry professionals focused on this group,” she said.

An excerpt from a sextortion tutorial from a Com-based Telegram channel. Image: Unit 221B.

Nixon knows a thing or two about being threatened by SLSH: For the past several months, the group’s Telegram channels have been replete with threats of physical violence against her, against Yours Truly, and against other security researchers. These threats, she said, are just another way the group seeks to generate media attention and achieve a veneer of credibility, but they are useful as indicators of compromise because SLSH members tend to name drop and malign security researchers even in their communications with victims.

“Watch for the following behaviors in their communications to you or their public statements,” Nixon said. “Repeated abusive mentions of Allison Nixon (or “A.N”), Unit 221B, or cybersecurity journalists—especially Brian Krebs—or any other cybersecurity employee, or cybersecurity company. Any threats to kill, or commit terrorism, or violence against internal employees, cybersecurity employees, investigators, and journalists.”

Unit 221B says that while the pressure campaign during an extortion attempt may be traumatizing to employees, executives, and their family members, entering into drawn-out negotiations with SLSH incentivizes the group to increase the level of harm and risk, which could include the physical safety of employees and their families.

“The breached data will never go back to the way it was, but we can assure you that the harassment will end,” Nixon said. “So, your decision to pay should be a separate issue from the harassment. We believe that when you separate these issues, you will objectively see that the best course of action to protect your interests, in both the short and long term, is to refuse payment.”

Cyber Security

Who Operates the Badbox 2.0 Botnet? – Krebs on Security

The cybercriminals in control of Kimwolf — a disruptive botnet that has infected more than 2 million devices — recently shared a screenshot indicating they’d compromised the control panel for Badbox 2.0, a vast China-based botnet powered by malicious software that comes pre-installed on many Android TV streaming boxes. Both the FBI and Google say they are hunting for the people behind Badbox 2.0, and thanks to bragging by the Kimwolf botmasters we may now have a much clearer idea about that.

Our first story of 2026, The Kimwolf Botnet is Stalking Your Local Network, detailed the unique and highly invasive methods Kimwolf uses to spread. The story warned that the vast majority of Kimwolf infected systems were unofficial Android TV boxes that are typically marketed as a way to watch unlimited (pirated) movie and TV streaming services for a one-time fee.

Our January 8 story, Who Benefitted from the Aisuru and Kimwolf Botnets?, cited multiple sources saying the current administrators of Kimwolf went by the nicknames “Dort” and “Snow.” Earlier this month, a close former associate of Dort and Snow shared what they said was a screenshot the Kimwolf botmasters had taken while logged in to the Badbox 2.0 botnet control panel.

That screenshot, a portion of which is shown below, shows seven authorized users of the control panel, including one that doesn’t quite match the others: According to my source, the account “ABCD” (the one that is logged in and listed in the top right of the screenshot) belongs to Dort, who somehow figured out how to add their email address as a valid user of the Badbox 2.0 botnet.

The control panel for the Badbox 2.0 botnet lists seven authorized users and their email addresses. Click to enlarge.

Badbox has a storied history that well predates Kimwolf’s rise in October 2025. In July 2025, Google filed a “John Doe” lawsuit (PDF) against 25 unidentified defendants accused of operating Badbox 2.0, which Google described as a botnet of over ten million unsanctioned Android streaming devices engaged in advertising fraud. Google said Badbox 2.0, in addition to compromising multiple types of devices prior to purchase, also can infect devices by requiring the download of malicious apps from unofficial marketplaces.

Google’s lawsuit came on the heels of a June 2025 advisory from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which warned that cyber criminals were gaining unauthorized access to home networks by either configuring the products with malware prior to the user’s purchase, or infecting the device as it downloads required applications that contain backdoors — usually during the set-up process.

The FBI said Badbox 2.0 was discovered after the original Badbox campaign was disrupted in 2024. The original Badbox was identified in 2023, and primarily consisted of Android operating system devices (TV boxes) that were compromised with backdoor malware prior to purchase.

KrebsOnSecurity was initially skeptical of the claim that the Kimwolf botmasters had hacked the Badbox 2.0 botnet. That is, until we began digging into the history of the qq.com email addresses in the screenshot above.

CATHEAD

An online search for the address 34557257@qq.com (pictured in the screenshot above as the user “Chen“) shows it is listed as a point of contact for a number of China-based technology companies, including:

–Beijing Hong Dake Wang Science & Technology Co Ltd.

–Beijing Hengchuang Vision Mobile Media Technology Co. Ltd.

–Moxin Beijing Science and Technology Co. Ltd.

The website for Beijing Hong Dake Wang Science is asmeisvip[.]net, a domain that was flagged in a March 2025 report by HUMAN Security as one of several dozen sites tied to the distribution and management of the Badbox 2.0 botnet. Ditto for moyix[.]com, a domain associated with Beijing Hengchuang Vision Mobile.

A search at the breach tracking service Constella Intelligence finds 34557257@qq.com at one point used the password “cdh76111.” Pivoting on that password in Constella shows it is known to have been used by just two other email accounts: daihaic@gmail.com and cathead@gmail.com.

Constella found cathead@gmail.com registered an account at jd.com (China’s largest online retailer) in 2021 under the name “陈代海,” which translates to “Chen Daihai.” According to DomainTools.com, the name Chen Daihai is present in the original registration records (2008) for moyix[.]com, along with the email address cathead@astrolink[.]cn.

Incidentally, astrolink[.]cn also is among the Badbox 2.0 domains identified in HUMAN Security’s 2025 report. DomainTools finds cathead@astrolink[.]cn was used to register more than a dozen domains, including vmud[.]net, yet another Badbox 2.0 domain tagged by HUMAN Security.

XAVIER

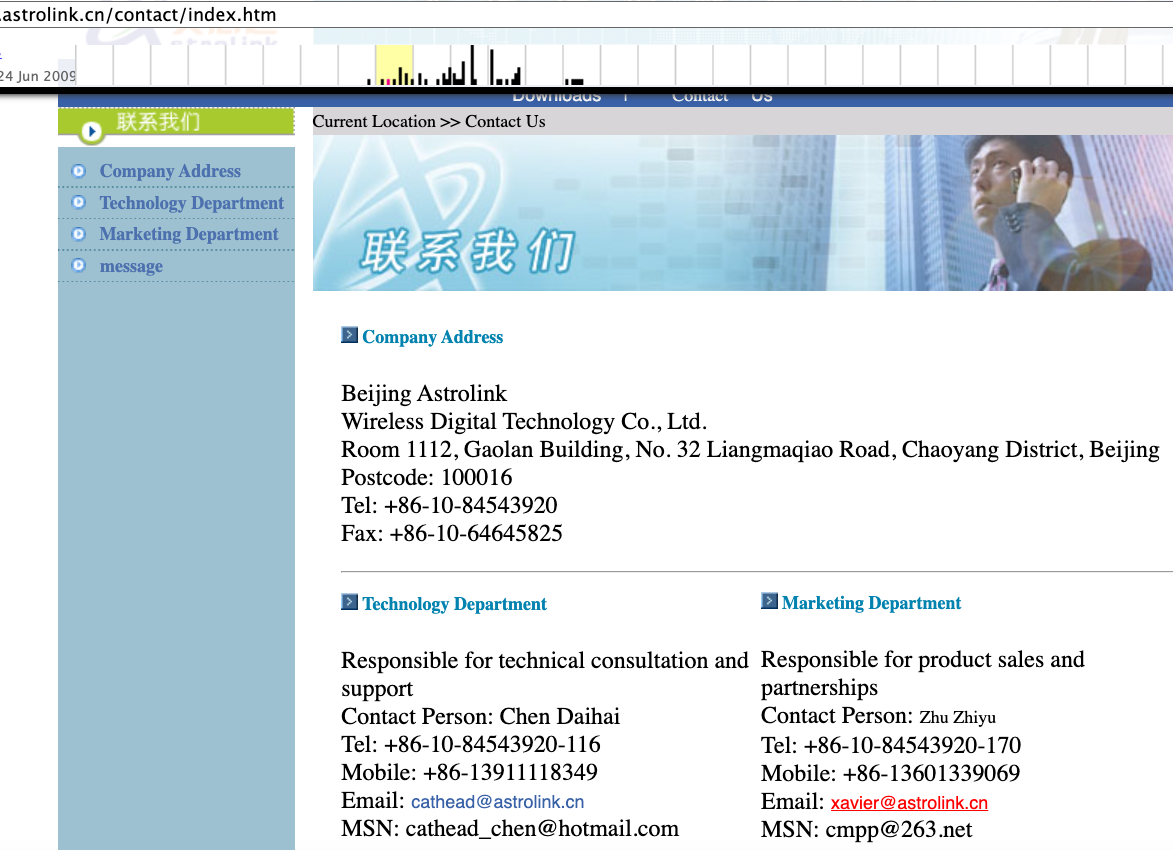

A cached copy of astrolink[.]cn preserved at archive.org shows the website belongs to a mobile app development company whose full name is Beijing Astrolink Wireless Digital Technology Co. Ltd. The archived website reveals a “Contact Us” page that lists a Chen Daihai as part of the company’s technology department. The other person featured on that contact page is Zhu Zhiyu, and their email address is listed as xavier@astrolink[.]cn.

A Google-translated version of Astrolink’s website, circa 2009. Image: archive.org.

Astute readers will notice that the user Mr.Zhu in the Badbox 2.0 panel used the email address xavierzhu@qq.com. Searching this address in Constella reveals a jd.com account registered in the name of Zhu Zhiyu. A rather unique password used by this account matches the password used by the address xavierzhu@gmail.com, which DomainTools finds was the original registrant of astrolink[.]cn.

ADMIN

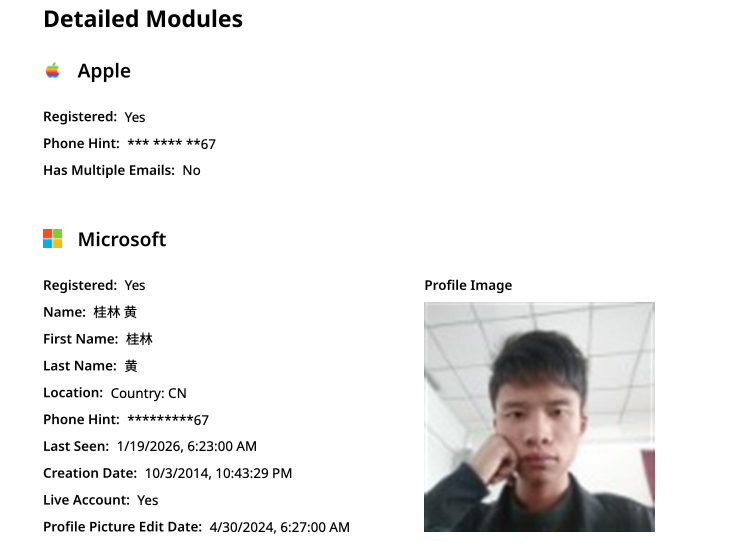

The very first account listed in the Badbox 2.0 panel — “admin,” registered in November 2020 — used the email address 189308024@qq.com. DomainTools shows this email is found in the 2022 registration records for the domain guilincloud[.]cn, which includes the registrant name “Huang Guilin.”

Constella finds 189308024@qq.com is associated with the China phone number 18681627767. The open-source intelligence platform osint.industries reveals this phone number is connected to a Microsoft profile created in 2014 under the name Guilin Huang (桂林 黄). The cyber intelligence platform Spycloud says that phone number was used in 2017 to create an account at the Chinese social media platform Weibo under the username “h_guilin.”

The public information attached to Guilin Huang’s Microsoft account, according to the breach tracking service osintindustries.com.

The remaining three users and corresponding qq.com email addresses were all connected to individuals in China. However, none of them (nor Mr. Huang) had any apparent connection to the entities created and operated by Chen Daihai and Zhu Zhiyu — or to any corporate entities for that matter. Also, none of these individuals responded to requests for comment.

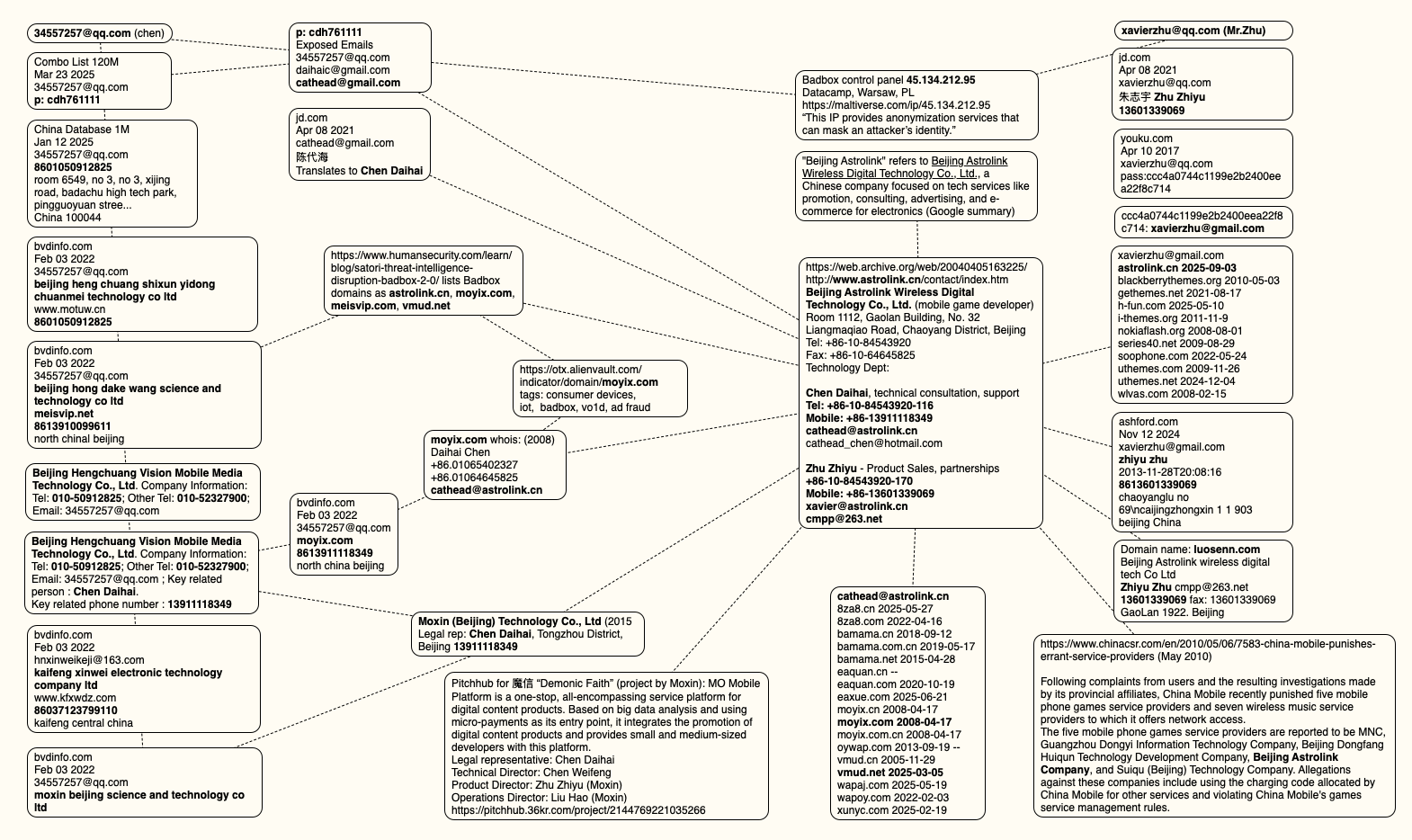

The mind map below includes search pivots on the email addresses, company names and phone numbers that suggest a connection between Chen Daihai, Zhu Zhiyu, and Badbox 2.0.

This mind map includes search pivots on the email addresses, company names and phone numbers that appear to connect Chen Daihai and Zhu Zhiyu to Badbox 2.0. Click to enlarge.

UNAUTHORIZED ACCESS

The idea that the Kimwolf botmasters could have direct access to the Badbox 2.0 botnet is a big deal, but explaining exactly why that is requires some background on how Kimwolf spreads to new devices. The botmasters figured out they could trick residential proxy services into relaying malicious commands to vulnerable devices behind the firewall on the unsuspecting user’s local network.

The vulnerable systems sought out by Kimwolf are primarily Internet of Things (IoT) devices like unsanctioned Android TV boxes and digital photo frames that have no discernible security or authentication built-in. Put simply, if you can communicate with these devices, you can compromise them with a single command.

Our January 2 story featured research from the proxy-tracking firm Synthient, which alerted 11 different residential proxy providers that their proxy endpoints were vulnerable to being abused for this kind of local network probing and exploitation.

Most of those vulnerable proxy providers have since taken steps to prevent customers from going upstream into the local networks of residential proxy endpoints, and it appeared that Kimwolf would no longer be able to quickly spread to millions of devices simply by exploiting some residential proxy provider.

However, the source of that Badbox 2.0 screenshot said the Kimwolf botmasters had an ace up their sleeve the whole time: Secret access to the Badbox 2.0 botnet control panel.

“Dort has gotten unauthorized access,” the source said. “So, what happened is normal proxy providers patched this. But Badbox doesn’t sell proxies by itself, so it’s not patched. And as long as Dort has access to Badbox, they would be able to load” the Kimwolf malware directly onto TV boxes associated with Badbox 2.0.

The source said it isn’t clear how Dort gained access to the Badbox botnet panel. But it’s unlikely that Dort’s existing account will persist for much longer: All of our notifications to the qq.com email addresses listed in the control panel screenshot received a copy of that image, as well as questions about the apparently rogue ABCD account.

-

Fintech6 months ago

Fintech6 months agoRace to Instant Onboarding Accelerates as FDIC OKs Pre‑filled Forms | PYMNTS.com

-

Cyber Security7 months ago

Cyber Security7 months agoHackers Use GitHub Repositories to Host Amadey Malware and Data Stealers, Bypassing Filters

-

Fintech7 months ago

DAT to Acquire Convoy Platform to Expand Freight-Matching Network’s Capabilities | PYMNTS.com

-

Fintech5 months ago

Fintech5 months agoID.me Raises $340 Million to Expand Digital Identity Solutions | PYMNTS.com

-

Fintech4 months ago

Fintech4 months agoTracking the Convergence of Payments and Digital Identity | PYMNTS.com

-

Artificial Intelligence7 months ago

Artificial Intelligence7 months agoNothing Phone 3 review: flagship-ish

-

Fintech5 months ago

Esh Bank Unveils Experience That Includes Revenue Sharing With Customers | PYMNTS.com

-

Artificial Intelligence7 months ago

Artificial Intelligence7 months agoThe best Android phones