Cyber Security

Kimwolf Botnet Lurking in Corporate, Govt. Networks – Krebs on Security

A new Internet-of-Things (IoT) botnet called Kimwolf has spread to more than 2 million devices, forcing infected systems to participate in massive distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks and to relay other malicious and abusive Internet traffic. Kimwolf’s ability to scan the local networks of compromised systems for other IoT devices to infect makes it a sobering threat to organizations, and new research reveals Kimwolf is surprisingly prevalent in government and corporate networks.

Image: Shutterstock, @Elzicon.

Kimwolf grew rapidly in the waning months of 2025 by tricking various “residential proxy” services into relaying malicious commands to devices on the local networks of those proxy endpoints. Residential proxies are sold as a way to anonymize and localize one’s Web traffic to a specific region, and the biggest of these services allow customers to route their Internet activity through devices in virtually any country or city around the globe.

The malware that turns one’s Internet connection into a proxy node is often quietly bundled with various mobile apps and games, and it typically forces the infected device to relay malicious and abusive traffic — including ad fraud, account takeover attempts, and mass content-scraping.

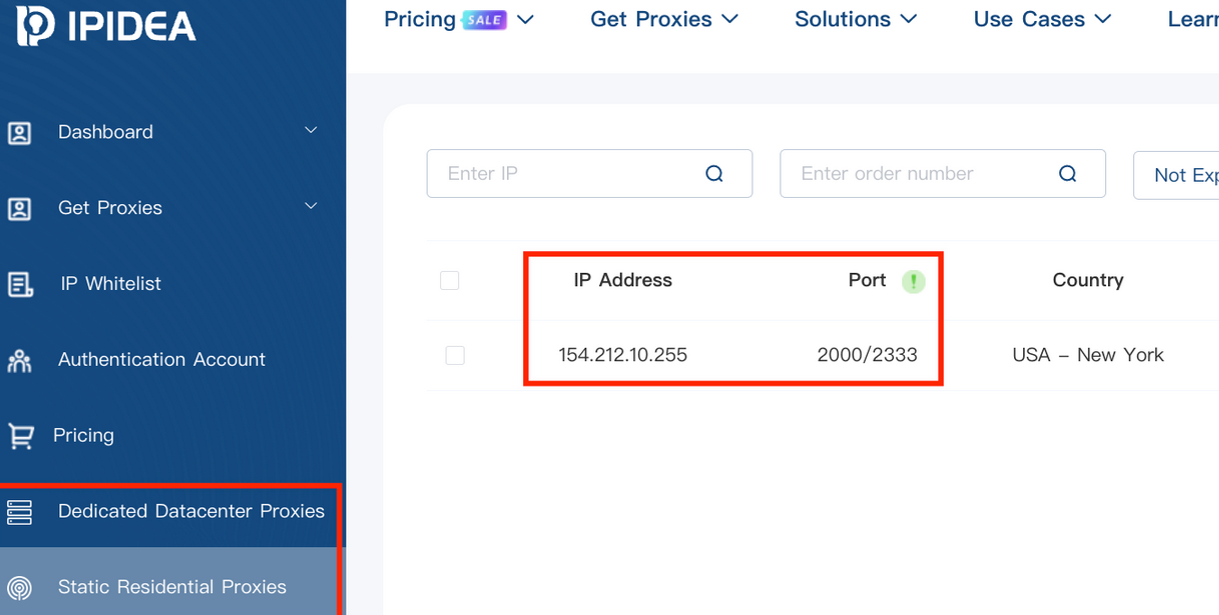

Kimwolf mainly targeted proxies from IPIDEA, a Chinese service that has millions of proxy endpoints for rent on any given week. The Kimwolf operators discovered they could forward malicious commands to the internal networks of IPIDEA proxy endpoints, and then programmatically scan for and infect other vulnerable devices on each endpoint’s local network.

Most of the systems compromised through Kimwolf’s local network scanning have been unofficial Android TV streaming boxes. These are typically Android Open Source Project devices — not Android TV OS devices or Play Protect certified Android devices — and they are generally marketed as a way to watch unlimited (read:pirated) video content from popular subscription streaming services for a one-time fee.

However, a great many of these TV boxes ship to consumers with residential proxy software pre-installed. What’s more, they have no real security or authentication built-in: If you can communicate directly with the TV box, you can also easily compromise it with malware.

While IPIDEA and other affected proxy providers recently have taken steps to block threats like Kimwolf from going upstream into their endpoints (reportedly with varying degrees of success), the Kimwolf malware remains on millions of infected devices.

A screenshot of IPIDEA’s proxy service.

Kimwolf’s close association with residential proxy networks and compromised Android TV boxes might suggest we’d find relatively few infections on corporate networks. However, the security firm Infoblox said a recent review of its customer traffic found nearly 25 percent of them made a query to a Kimwolf-related domain name since October 1, 2025, when the botnet first showed signs of life.

Infoblox found the affected customers are based all over the world and in a wide range of industry verticals, from education and healthcare to government and finance.

“To be clear, this suggests that nearly 25% of customers had at least one device that was an endpoint in a residential proxy service targeted by Kimwolf operators,” Infoblox explained. “Such a device, maybe a phone or a laptop, was essentially co-opted by the threat actor to probe the local network for vulnerable devices. A query means a scan was made, not that new devices were compromised. Lateral movement would fail if there were no vulnerable devices to be found or if the DNS resolution was blocked.”

Synthient, a startup that tracks proxy services and was the first to disclose on January 2 the unique methods Kimwolf uses to spread, found proxy endpoints from IPIDEA were present in alarming numbers at government and academic institutions worldwide. Synthient said it spied at least 33,000 affected Internet addresses at universities and colleges, and nearly 8,000 IPIDEA proxies within various U.S. and foreign government networks.

The top 50 domain names sought out by users of IPIDEA’s residential proxy service, according to Synthient.

In a webinar on January 16, experts at the proxy tracking service Spur profiled Internet addresses associated with IPIDEA and 10 other proxy services that were thought to be vulnerable to Kimwolf’s tricks. Spur found residential proxies in nearly 300 government owned and operated networks, 318 utility companies, 166 healthcare companies or hospitals, and 141 companies in banking and finance.

“I looked at the 298 [government] owned and operated [networks], and so many of them were DoD [U.S. Department of Defense], which is kind of terrifying that DoD has IPIDEA and these other proxy services located inside of it,” Spur Co-Founder Riley Kilmer said. “I don’t know how these enterprises have these networks set up. It could be that [infected devices] are segregated on the network, that even if you had local access it doesn’t really mean much. However, it’s something to be aware of. If a device goes in, anything that device has access to the proxy would have access to.”

Kilmer said Kimwolf demonstrates how a single residential proxy infection can quickly lead to bigger problems for organizations that are harboring unsecured devices behind their firewalls, noting that proxy services present a potentially simple way for attackers to probe other devices on the local network of a targeted organization.

“If you know you have [proxy] infections that are located in a company, you can chose that [network] to come out of and then locally pivot,” Kilmer said. “If you have an idea of where to start or look, now you have a foothold in a company or an enterprise based on just that.”

This is the third story in our series on the Kimwolf botnet. Next week, we’ll shed light on the myriad China-based individuals and companies connected to the Badbox 2.0 botnet, the collective name given to a vast number of Android TV streaming box models that ship with no discernible security or authentication built-in, and with residential proxy malware pre-installed.

Further reading:

The Kimwolf Botnet is Stalking Your Local Network

Who Benefitted from the Aisuru and Kimwolf Botnets?

A Broken System Fueling Botnets (Synthient).

Cyber Security

Please Don’t Feed the Scattered Lapsus Shiny Hunters – Krebs on Security

A prolific data ransom gang that calls itself Scattered Lapsus Shiny Hunters (SLSH) has a distinctive playbook when it seeks to extort payment from victim firms: Harassing, threatening and even swatting executives and their families, all while notifying journalists and regulators about the extent of the intrusion. Some victims reportedly are paying — perhaps as much to contain the stolen data as to stop the escalating personal attacks. But a top SLSH expert warns that engaging at all beyond a “We’re not paying” response only encourages further harassment, noting that the group’s fractious and unreliable history means the only winning move is not to pay.

Image: Shutterstock.com, @Mungujakisa

Unlike traditional, highly regimented Russia-based ransomware affiliate groups, SLSH is an unruly and somewhat fluid English-language extortion gang that appears uninterested in building a reputation of consistent behavior whereby victims might have some measure of confidence that the criminals will keep their word if paid.

That’s according to Allison Nixon, director of research at the New York City based security consultancy Unit 221. Nixon has been closely tracking the criminal group and individual members as they bounce between various Telegram channels used to extort and harass victims, and she said SLSH differs from traditional data ransom groups in other important ways that argue against trusting them to do anything they say they’ll do — such as destroying stolen data.

Like SLSH, many traditional Russian ransomware groups have employed high-pressure tactics to force payment in exchange for a decryption key and/or a promise to delete stolen data, such as publishing a dark web shaming blog with samples of stolen data next to a countdown clock, or notifying journalists and board members of the victim company. But Nixon said the extortion from SLSH quickly escalates way beyond that — to threats of physical violence against executives and their families, DDoS attacks on the victim’s website, and repeated email-flooding campaigns.

SLSH is known for breaking into companies by phishing employees over the phone, and using the purloined access to steal sensitive internal data. In a January 30 blog post, Google’s security forensics firm Mandiant said SLSH’s most recent extortion attacks stem from incidents spanning early to mid-January 2026, when SLSH members pretended to be IT staff and called employees at targeted victim organizations claiming that the company was updating MFA settings.

“The threat actor directed the employees to victim-branded credential harvesting sites to capture their SSO credentials and MFA codes, and then registered their own device for MFA,” the blog post explained.

Victims often first learn of the breach when their brand name is uttered on whatever ephemeral new public Telegram group chat SLSH is using to threaten, extort and harass their prey. According to Nixon, the coordinated harassment on the SLSH Telegram channels is part of a well-orchestrated strategy to overwhelm the victim organization by manufacturing humiliation that pushes them over the threshold to pay.

Nixon said multiple executives at targeted organizations have been subject to “swatting” attacks, wherein SLSH communicated a phony bomb threat or hostage situation at the target’s address in the hopes of eliciting a heavily armed police response at their home or place of work.

“A big part of what they’re doing to victims is the psychological aspect of it, like harassing executives’ kids and threatening the board of the company,” Nixon told KrebsOnSecurity. “And while these victims are getting extortion demands, they’re simultaneously getting outreach from media outlets saying, ‘Hey, do you have any comments on the bad things we’re going to write about you.”

Nixon argues that no one should negotiate with SLSH because the group has demonstrated a willingness to extort victims based on promises that it has no intention to keep. Nixon points out that all of SLSH’s known members hail from The Com, shorthand for a constellation of cybercrime-focused Discord and Telegram communities which serve as a kind of distributed social network that facilitates instant collaboration.

Nixon said Com-based extortion groups tend to instigate feuds and drama between group members, leading to lying, betrayals, credibility destroying behavior, backstabbing, and sabotaging each other.

“With this type of ongoing dysfunction, often compounding by substance abuse, these threat actors often aren’t able to act with the core goal in mind of completing a successful, strategic ransom operation,” Nixon said. “They continually lose control with outbursts that put their strategy and operational security at risk, which severely limits their ability to build a professional, scalable, and sophisticated criminal organization network for continued successful ransoms – unlike other, more tenured and professional criminal organizations focused on ransomware alone.”

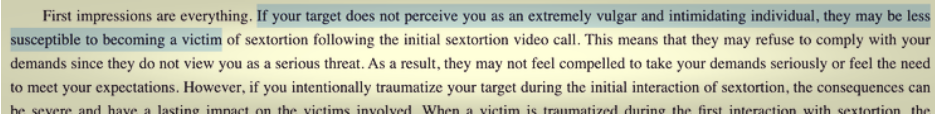

Intrusions from established ransomware groups typically center around encryption/decryption malware that mostly stays on the affected machine. In contrast, Nixon said, ransom from a Com group is often structured the same as violent sextortion schemes against minors, wherein members of The Com will steal damaging information, threaten to release it, and “promise” to delete it if the victim complies without any guarantee or technical proof point that they will keep their word. She writes:

The SLSH group steals a significant amount of corporate data, and on the day of issuing the ransom notification, they line up a number of harassment attacks to be delivered simultaneously with the ransom. This can include swatting, DDOS, email/SMS/call floods, negative PR, complaints sent to authority figures in and above the company, and so on. Then, during the negotiation process, they lay on the pressure with more harassment- never allowing too much time to pass before a new harassment attack.

What they negotiate for is the promise to not leak the data if you pay the ransom. This promise places a lot of trust in the extorter, because they cannot prove they deleted the data, and we believe they don’t intend to delete the data. Paying provides them vital information about the value of the stolen dataset which we believe will be useful for fraud operations after this wave is complete.

A key component of SLSH’s efforts to convince victims to pay, Nixon said, involves manipulating the media into hyping the threat posed by this group. This approach also borrows a page from the playbook of sextortion attacks, she said, which encourages predators to keep targets continuously engaged and worrying about the consequences of non-compliance.

“On days where SLSH had no substantial criminal ‘win’ to announce, they focused on announcing death threats and harassment to keep law enforcement, journalists, and cybercrime industry professionals focused on this group,” she said.

An excerpt from a sextortion tutorial from a Com-based Telegram channel. Image: Unit 221B.

Nixon knows a thing or two about being threatened by SLSH: For the past several months, the group’s Telegram channels have been replete with threats of physical violence against her, against Yours Truly, and against other security researchers. These threats, she said, are just another way the group seeks to generate media attention and achieve a veneer of credibility, but they are useful as indicators of compromise because SLSH members tend to name drop and malign security researchers even in their communications with victims.

“Watch for the following behaviors in their communications to you or their public statements,” Nixon said. “Repeated abusive mentions of Allison Nixon (or “A.N”), Unit 221B, or cybersecurity journalists—especially Brian Krebs—or any other cybersecurity employee, or cybersecurity company. Any threats to kill, or commit terrorism, or violence against internal employees, cybersecurity employees, investigators, and journalists.”

Unit 221B says that while the pressure campaign during an extortion attempt may be traumatizing to employees, executives, and their family members, entering into drawn-out negotiations with SLSH incentivizes the group to increase the level of harm and risk, which could include the physical safety of employees and their families.

“The breached data will never go back to the way it was, but we can assure you that the harassment will end,” Nixon said. “So, your decision to pay should be a separate issue from the harassment. We believe that when you separate these issues, you will objectively see that the best course of action to protect your interests, in both the short and long term, is to refuse payment.”

Cyber Security

Who Operates the Badbox 2.0 Botnet? – Krebs on Security

The cybercriminals in control of Kimwolf — a disruptive botnet that has infected more than 2 million devices — recently shared a screenshot indicating they’d compromised the control panel for Badbox 2.0, a vast China-based botnet powered by malicious software that comes pre-installed on many Android TV streaming boxes. Both the FBI and Google say they are hunting for the people behind Badbox 2.0, and thanks to bragging by the Kimwolf botmasters we may now have a much clearer idea about that.

Our first story of 2026, The Kimwolf Botnet is Stalking Your Local Network, detailed the unique and highly invasive methods Kimwolf uses to spread. The story warned that the vast majority of Kimwolf infected systems were unofficial Android TV boxes that are typically marketed as a way to watch unlimited (pirated) movie and TV streaming services for a one-time fee.

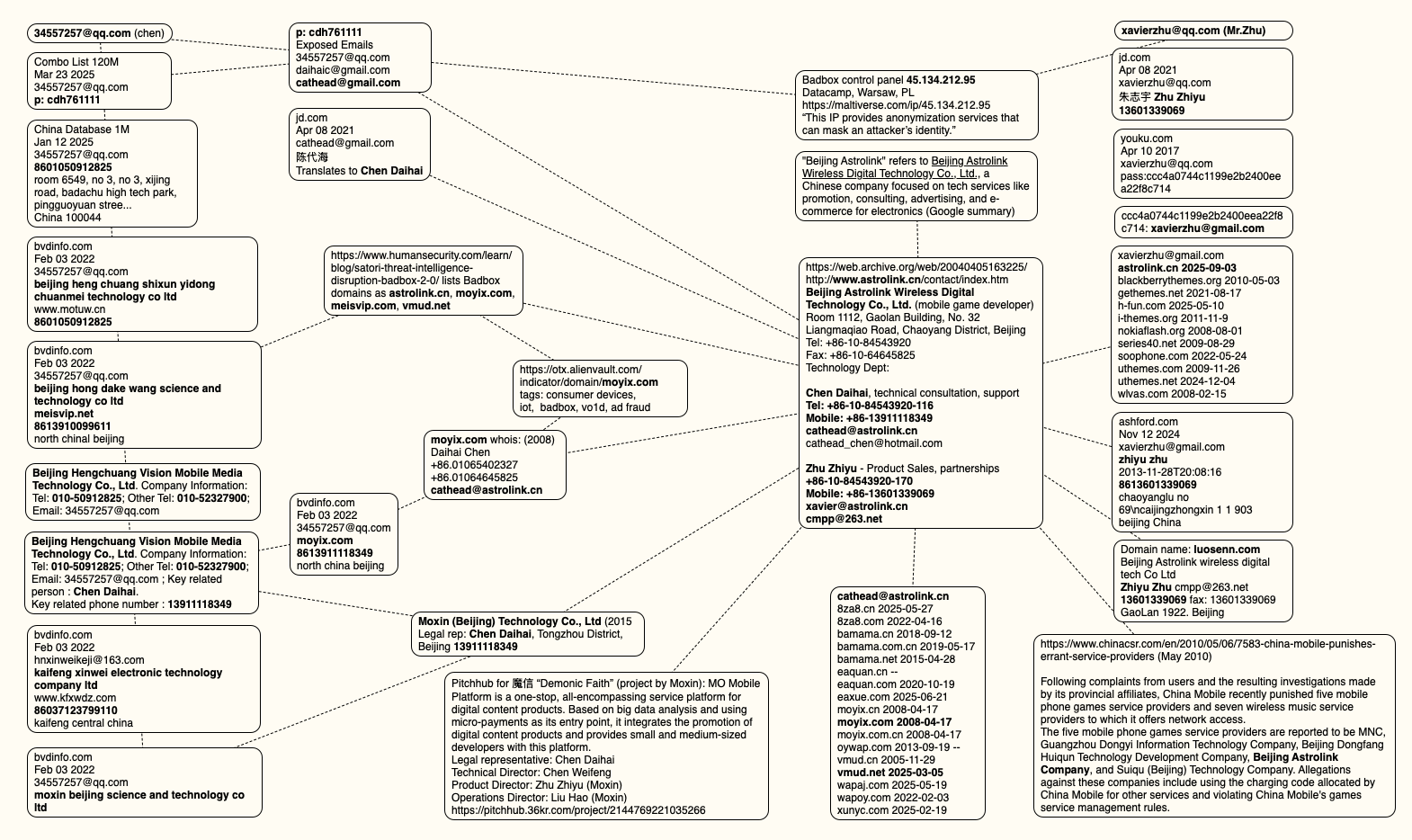

Our January 8 story, Who Benefitted from the Aisuru and Kimwolf Botnets?, cited multiple sources saying the current administrators of Kimwolf went by the nicknames “Dort” and “Snow.” Earlier this month, a close former associate of Dort and Snow shared what they said was a screenshot the Kimwolf botmasters had taken while logged in to the Badbox 2.0 botnet control panel.

That screenshot, a portion of which is shown below, shows seven authorized users of the control panel, including one that doesn’t quite match the others: According to my source, the account “ABCD” (the one that is logged in and listed in the top right of the screenshot) belongs to Dort, who somehow figured out how to add their email address as a valid user of the Badbox 2.0 botnet.

The control panel for the Badbox 2.0 botnet lists seven authorized users and their email addresses. Click to enlarge.

Badbox has a storied history that well predates Kimwolf’s rise in October 2025. In July 2025, Google filed a “John Doe” lawsuit (PDF) against 25 unidentified defendants accused of operating Badbox 2.0, which Google described as a botnet of over ten million unsanctioned Android streaming devices engaged in advertising fraud. Google said Badbox 2.0, in addition to compromising multiple types of devices prior to purchase, also can infect devices by requiring the download of malicious apps from unofficial marketplaces.

Google’s lawsuit came on the heels of a June 2025 advisory from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which warned that cyber criminals were gaining unauthorized access to home networks by either configuring the products with malware prior to the user’s purchase, or infecting the device as it downloads required applications that contain backdoors — usually during the set-up process.

The FBI said Badbox 2.0 was discovered after the original Badbox campaign was disrupted in 2024. The original Badbox was identified in 2023, and primarily consisted of Android operating system devices (TV boxes) that were compromised with backdoor malware prior to purchase.

KrebsOnSecurity was initially skeptical of the claim that the Kimwolf botmasters had hacked the Badbox 2.0 botnet. That is, until we began digging into the history of the qq.com email addresses in the screenshot above.

CATHEAD

An online search for the address 34557257@qq.com (pictured in the screenshot above as the user “Chen“) shows it is listed as a point of contact for a number of China-based technology companies, including:

–Beijing Hong Dake Wang Science & Technology Co Ltd.

–Beijing Hengchuang Vision Mobile Media Technology Co. Ltd.

–Moxin Beijing Science and Technology Co. Ltd.

The website for Beijing Hong Dake Wang Science is asmeisvip[.]net, a domain that was flagged in a March 2025 report by HUMAN Security as one of several dozen sites tied to the distribution and management of the Badbox 2.0 botnet. Ditto for moyix[.]com, a domain associated with Beijing Hengchuang Vision Mobile.

A search at the breach tracking service Constella Intelligence finds 34557257@qq.com at one point used the password “cdh76111.” Pivoting on that password in Constella shows it is known to have been used by just two other email accounts: daihaic@gmail.com and cathead@gmail.com.

Constella found cathead@gmail.com registered an account at jd.com (China’s largest online retailer) in 2021 under the name “陈代海,” which translates to “Chen Daihai.” According to DomainTools.com, the name Chen Daihai is present in the original registration records (2008) for moyix[.]com, along with the email address cathead@astrolink[.]cn.

Incidentally, astrolink[.]cn also is among the Badbox 2.0 domains identified in HUMAN Security’s 2025 report. DomainTools finds cathead@astrolink[.]cn was used to register more than a dozen domains, including vmud[.]net, yet another Badbox 2.0 domain tagged by HUMAN Security.

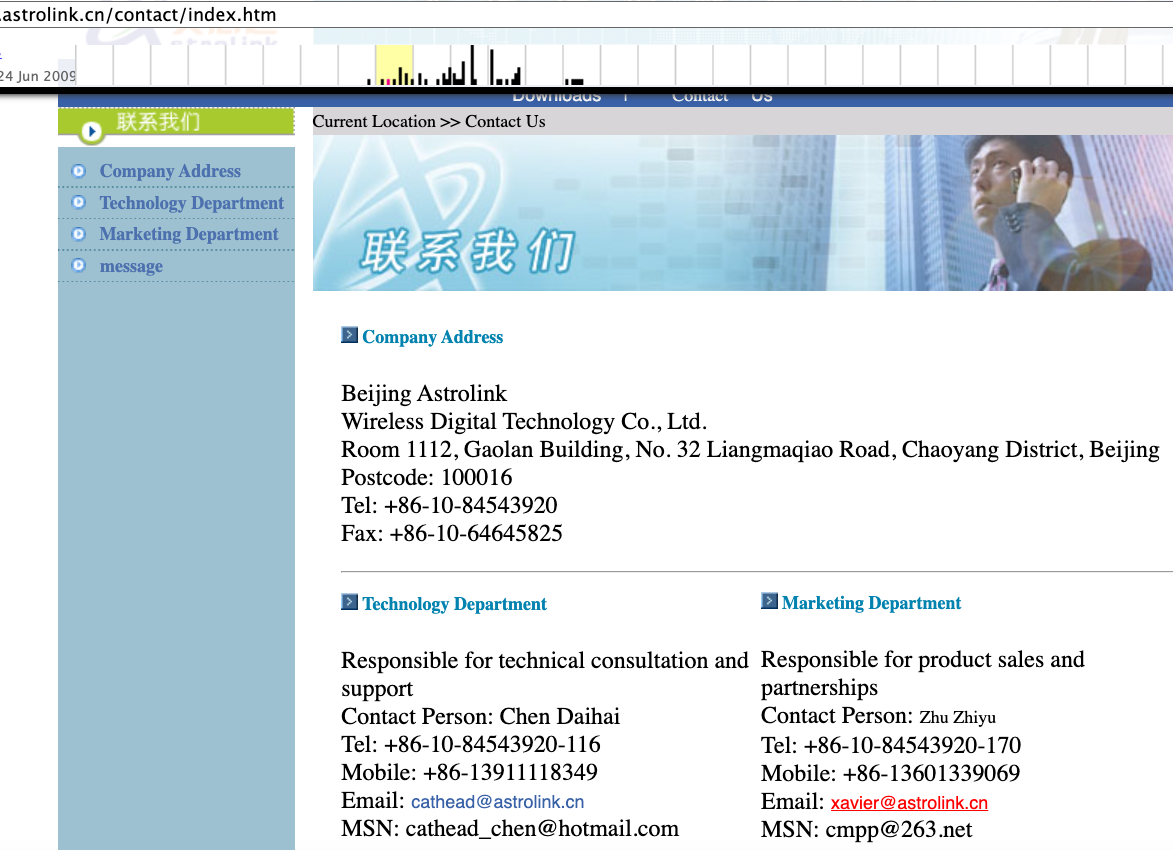

XAVIER

A cached copy of astrolink[.]cn preserved at archive.org shows the website belongs to a mobile app development company whose full name is Beijing Astrolink Wireless Digital Technology Co. Ltd. The archived website reveals a “Contact Us” page that lists a Chen Daihai as part of the company’s technology department. The other person featured on that contact page is Zhu Zhiyu, and their email address is listed as xavier@astrolink[.]cn.

A Google-translated version of Astrolink’s website, circa 2009. Image: archive.org.

Astute readers will notice that the user Mr.Zhu in the Badbox 2.0 panel used the email address xavierzhu@qq.com. Searching this address in Constella reveals a jd.com account registered in the name of Zhu Zhiyu. A rather unique password used by this account matches the password used by the address xavierzhu@gmail.com, which DomainTools finds was the original registrant of astrolink[.]cn.

ADMIN

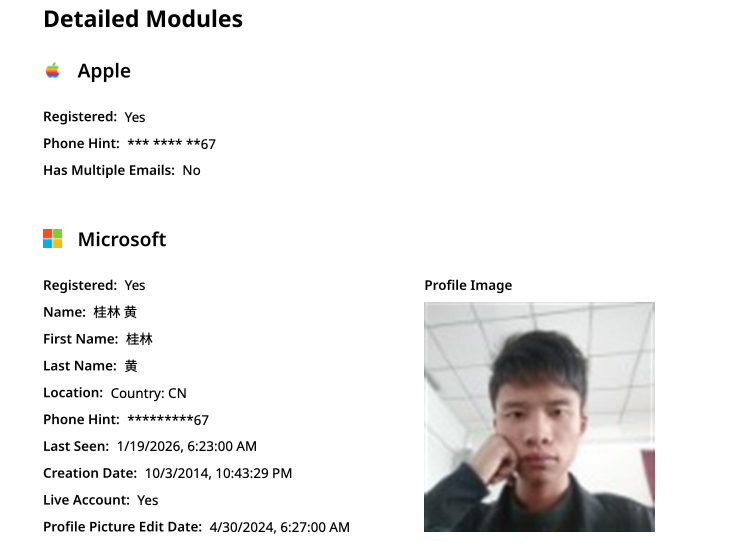

The very first account listed in the Badbox 2.0 panel — “admin,” registered in November 2020 — used the email address 189308024@qq.com. DomainTools shows this email is found in the 2022 registration records for the domain guilincloud[.]cn, which includes the registrant name “Huang Guilin.”

Constella finds 189308024@qq.com is associated with the China phone number 18681627767. The open-source intelligence platform osint.industries reveals this phone number is connected to a Microsoft profile created in 2014 under the name Guilin Huang (桂林 黄). The cyber intelligence platform Spycloud says that phone number was used in 2017 to create an account at the Chinese social media platform Weibo under the username “h_guilin.”

The public information attached to Guilin Huang’s Microsoft account, according to the breach tracking service osintindustries.com.

The remaining three users and corresponding qq.com email addresses were all connected to individuals in China. However, none of them (nor Mr. Huang) had any apparent connection to the entities created and operated by Chen Daihai and Zhu Zhiyu — or to any corporate entities for that matter. Also, none of these individuals responded to requests for comment.

The mind map below includes search pivots on the email addresses, company names and phone numbers that suggest a connection between Chen Daihai, Zhu Zhiyu, and Badbox 2.0.

This mind map includes search pivots on the email addresses, company names and phone numbers that appear to connect Chen Daihai and Zhu Zhiyu to Badbox 2.0. Click to enlarge.

UNAUTHORIZED ACCESS

The idea that the Kimwolf botmasters could have direct access to the Badbox 2.0 botnet is a big deal, but explaining exactly why that is requires some background on how Kimwolf spreads to new devices. The botmasters figured out they could trick residential proxy services into relaying malicious commands to vulnerable devices behind the firewall on the unsuspecting user’s local network.

The vulnerable systems sought out by Kimwolf are primarily Internet of Things (IoT) devices like unsanctioned Android TV boxes and digital photo frames that have no discernible security or authentication built-in. Put simply, if you can communicate with these devices, you can compromise them with a single command.

Our January 2 story featured research from the proxy-tracking firm Synthient, which alerted 11 different residential proxy providers that their proxy endpoints were vulnerable to being abused for this kind of local network probing and exploitation.

Most of those vulnerable proxy providers have since taken steps to prevent customers from going upstream into the local networks of residential proxy endpoints, and it appeared that Kimwolf would no longer be able to quickly spread to millions of devices simply by exploiting some residential proxy provider.

However, the source of that Badbox 2.0 screenshot said the Kimwolf botmasters had an ace up their sleeve the whole time: Secret access to the Badbox 2.0 botnet control panel.

“Dort has gotten unauthorized access,” the source said. “So, what happened is normal proxy providers patched this. But Badbox doesn’t sell proxies by itself, so it’s not patched. And as long as Dort has access to Badbox, they would be able to load” the Kimwolf malware directly onto TV boxes associated with Badbox 2.0.

The source said it isn’t clear how Dort gained access to the Badbox botnet panel. But it’s unlikely that Dort’s existing account will persist for much longer: All of our notifications to the qq.com email addresses listed in the control panel screenshot received a copy of that image, as well as questions about the apparently rogue ABCD account.

Cyber Security

Who Benefited from the Aisuru and Kimwolf Botnets? – Krebs on Security

Our first story of 2026 revealed how a destructive new botnet called Kimwolf has infected more than two million devices by mass-compromising a vast number of unofficial Android TV streaming boxes. Today, we’ll dig through digital clues left behind by the hackers, network operators and services that appear to have benefitted from Kimwolf’s spread.

On Dec. 17, 2025, the Chinese security firm XLab published a deep dive on Kimwolf, which forces infected devices to participate in distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks and to relay abusive and malicious Internet traffic for so-called “residential proxy” services.

The software that turns one’s device into a residential proxy is often quietly bundled with mobile apps and games. Kimwolf specifically targeted residential proxy software that is factory installed on more than a thousand different models of unsanctioned Android TV streaming devices. Very quickly, the residential proxy’s Internet address starts funneling traffic that is linked to ad fraud, account takeover attempts and mass content scraping.

The XLab report explained its researchers found “definitive evidence” that the same cybercriminal actors and infrastructure were used to deploy both Kimwolf and the Aisuru botnet — an earlier version of Kimwolf that also enslaved devices for use in DDoS attacks and proxy services.

XLab said it suspected since October that Kimwolf and Aisuru had the same author(s) and operators, based in part on shared code changes over time. But it said those suspicions were confirmed on December 8 when it witnessed both botnet strains being distributed by the same Internet address at 93.95.112[.]59.

Image: XLab.

RESI RACK

Public records show the Internet address range flagged by XLab is assigned to Lehi, Utah-based Resi Rack LLC. Resi Rack’s website bills the company as a “Premium Game Server Hosting Provider.” Meanwhile, Resi Rack’s ads on the Internet moneymaking forum BlackHatWorld refer to it as a “Premium Residential Proxy Hosting and Proxy Software Solutions Company.”

Resi Rack co-founder Cassidy Hales told KrebsOnSecurity his company received a notification on December 10 about Kimwolf using their network “that detailed what was being done by one of our customers leasing our servers.”

“When we received this email we took care of this issue immediately,” Hales wrote in response to an email requesting comment. “This is something we are very disappointed is now associated with our name and this was not the intention of our company whatsoever.”

The Resi Rack Internet address cited by XLab on December 8 came onto KrebsOnSecurity’s radar more than two weeks before that. Benjamin Brundage is founder of Synthient, a startup that tracks proxy services. In late October 2025, Brundage shared that the people selling various proxy services which benefitted from the Aisuru and Kimwolf botnets were doing so at a new Discord server called resi[.]to.

On November 24, 2025, a member of the resi-dot-to Discord channel shares an IP address responsible for proxying traffic over Android TV streaming boxes infected by the Kimwolf botnet.

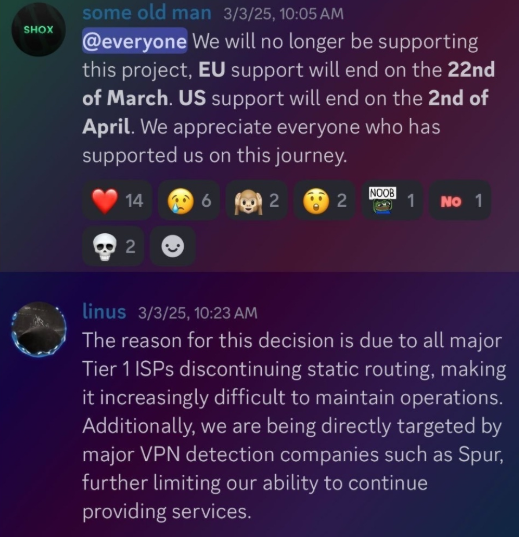

When KrebsOnSecurity joined the resi[.]to Discord channel in late October as a silent lurker, the server had fewer than 150 members, including “Shox” — the nickname used by Resi Rack’s co-founder Mr. Hales — and his business partner “Linus,” who did not respond to requests for comment.

Other members of the resi[.]to Discord channel would periodically post new IP addresses that were responsible for proxying traffic over the Kimwolf botnet. As the screenshot from resi[.]to above shows, that Resi Rack Internet address flagged by XLab was used by Kimwolf to direct proxy traffic as far back as November 24, if not earlier. All told, Synthient said it tracked at least seven static Resi Rack IP addresses connected to Kimwolf proxy infrastructure between October and December 2025.

Neither of Resi Rack’s co-owners responded to follow-up questions. Both have been active in selling proxy services via Discord for nearly two years. According to a review of Discord messages indexed by the cyber intelligence firm Flashpoint, Shox and Linus spent much of 2024 selling static “ISP proxies” by routing various Internet address blocks at major U.S. Internet service providers.

In February 2025, AT&T announced that effective July 31, 2025, it would no longer originate routes for network blocks that are not owned and managed by AT&T (other major ISPs have since made similar moves). Less than a month later, Shox and Linus told customers they would soon cease offering static ISP proxies as a result of these policy changes.

Shox and Linux, talking about their decision to stop selling ISP proxies.

DORT & SNOW

The stated owner of the resi[.]to Discord server went by the abbreviated username “D.” That initial appears to be short for the hacker handle “Dort,” a name that was invoked frequently throughout these Discord chats.

Dort’s profile on resi dot to.

This “Dort” nickname came up in KrebsOnSecurity’s recent conversations with “Forky,” a Brazilian man who acknowledged being involved in the marketing of the Aisuru botnet at its inception in late 2024. But Forky vehemently denied having anything to do with a series of massive and record-smashing DDoS attacks in the latter half of 2025 that were blamed on Aisuru, saying the botnet by that point had been taken over by rivals.

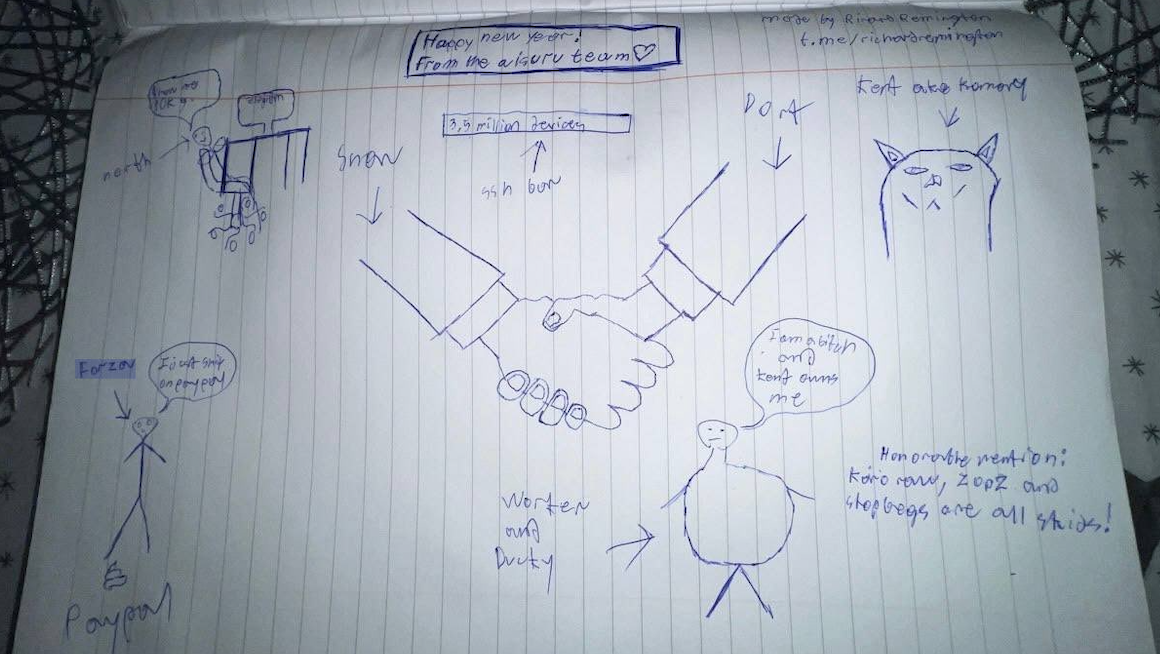

Forky asserts that Dort is a resident of Canada and one of at least two individuals currently in control of the Aisuru/Kimwolf botnet. The other individual Forky named as an Aisuru/Kimwolf botmaster goes by the nickname “Snow.”

On January 2 — just hours after our story on Kimwolf was published — the historical chat records on resi[.]to were erased without warning and replaced by a profanity-laced message for Synthient’s founder. Minutes after that, the entire server disappeared.

Later that same day, several of the more active members of the now-defunct resi[.]to Discord server moved to a Telegram channel where they posted Brundage’s personal information, and generally complained about being unable to find reliable “bulletproof” hosting for their botnet.

Hilariously, a user by the name “Richard Remington” briefly appeared in the group’s Telegram server to post a crude “Happy New Year” sketch that claims Dort and Snow are now in control of 3.5 million devices infected by Aisuru and/or Kimwolf. Richard Remington’s Telegram account has since been deleted, but it previously stated its owner operates a website that caters to DDoS-for-hire or “stresser” services seeking to test their firepower.

BYTECONNECT, PLAINPROXIES, AND 3XK TECH

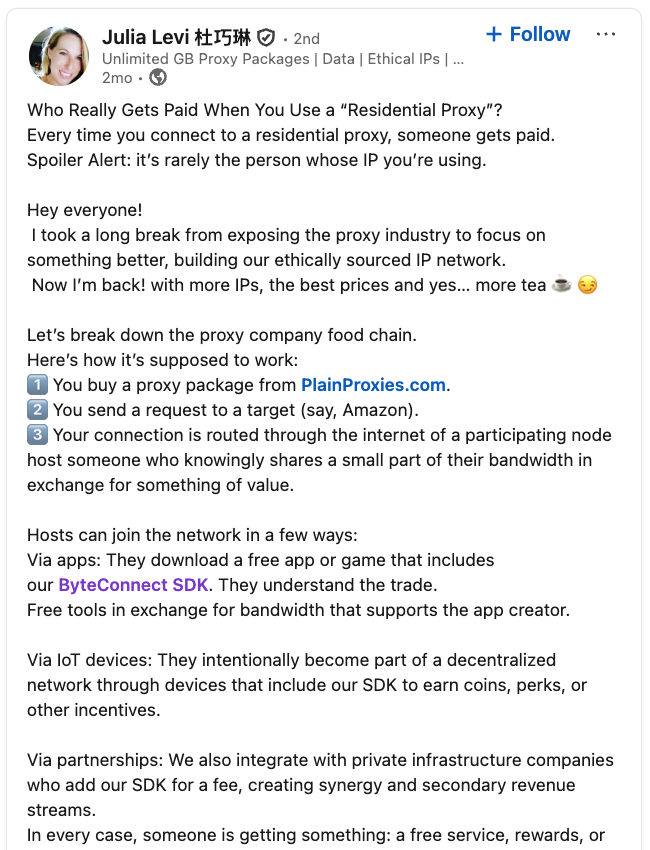

Reports from both Synthient and XLab found that Kimwolf was used to deploy programs that turned infected systems into Internet traffic relays for multiple residential proxy services. Among those was a component that installed a software development kit (SDK) called ByteConnect, which is distributed by a provider known as Plainproxies.

ByteConnect says it specializes in “monetizing apps ethically and free,” while Plainproxies advertises the ability to provide content scraping companies with “unlimited” proxy pools. However, Synthient said that upon connecting to ByteConnect’s SDK they instead observed a mass influx of credential-stuffing attacks targeting email servers and popular online websites.

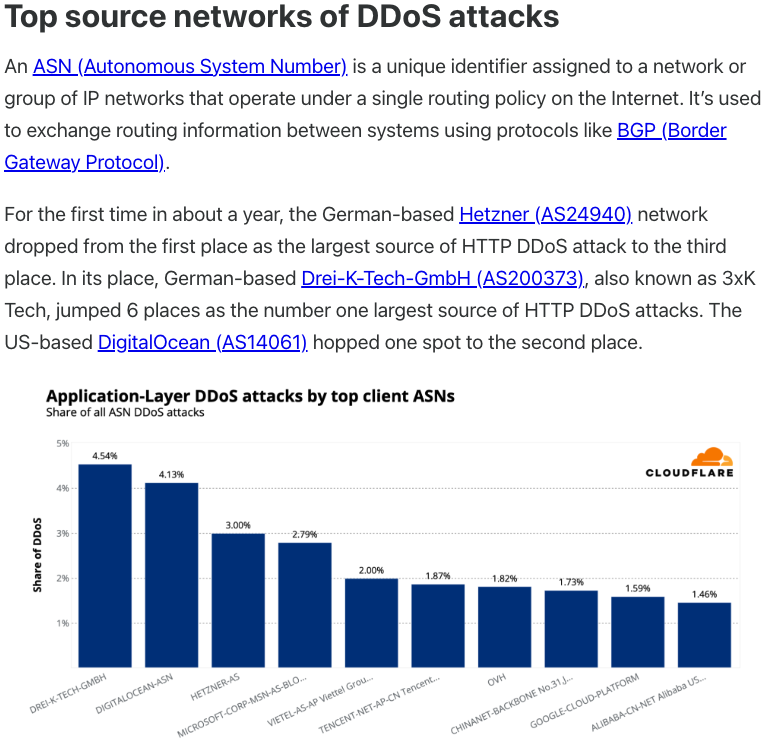

A search on LinkedIn finds the CEO of Plainproxies is Friedrich Kraft, whose resume says he is co-founder of ByteConnect Ltd. Public Internet routing records show Mr. Kraft also operates a hosting firm in Germany called 3XK Tech GmbH. Mr. Kraft did not respond to repeated requests for an interview.

In July 2025, Cloudflare reported that 3XK Tech (a.k.a. Drei-K-Tech) had become the Internet’s largest source of application-layer DDoS attacks. In November 2025, the security firm GreyNoise Intelligence found that Internet addresses on 3XK Tech were responsible for roughly three-quarters of the Internet scanning being done at the time for a newly discovered and critical vulnerability in security products made by Palo Alto Networks.

Source: Cloudflare’s Q2 2025 DDoS threat report.

LinkedIn has a profile for another Plainproxies employee, Julia Levi, who is listed as co-founder of ByteConnect. Ms. Levi did not respond to requests for comment. Her resume says she previously worked for two major proxy providers: Netnut Proxy Network, and Bright Data.

Synthient likewise said Plainproxies ignored their outreach, noting that the Byteconnect SDK continues to remain active on devices compromised by Kimwolf.

A post from the LinkedIn page of Plainproxies Chief Revenue Officer Julia Levi, explaining how the residential proxy business works.

MASKIFY

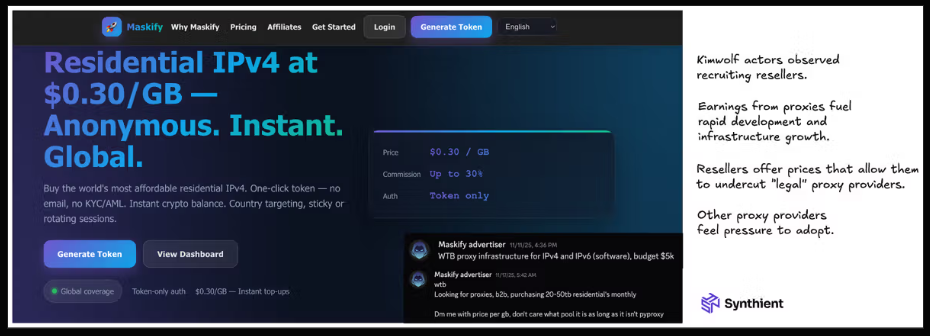

Synthient’s January 2 report said another proxy provider heavily involved in the sale of Kimwolf proxies was Maskify, which currently advertises on multiple cybercrime forums that it has more than six million residential Internet addresses for rent.

Maskify prices its service at a rate of 30 cents per gigabyte of data relayed through their proxies. According to Synthient, that price range is insanely low and is far cheaper than any other proxy provider in business today.

“Synthient’s Research Team received screenshots from other proxy providers showing key Kimwolf actors attempting to offload proxy bandwidth in exchange for upfront cash,” the Synthient report noted. “This approach likely helped fuel early development, with associated members spending earnings on infrastructure and outsourced development tasks. Please note that resellers know precisely what they are selling; proxies at these prices are not ethically sourced.”

Maskify did not respond to requests for comment.

The Maskify website. Image: Synthient.

BOTMASTERS LASH OUT

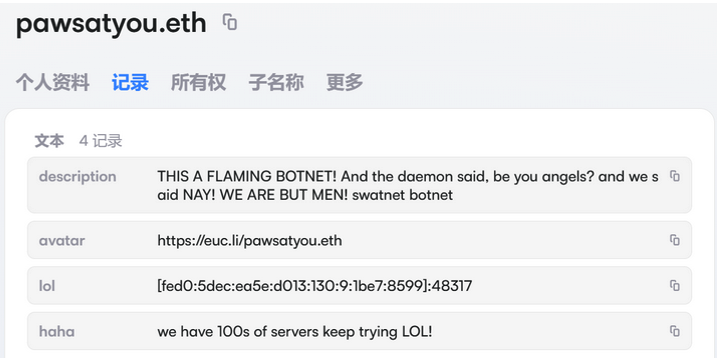

Hours after our first Kimwolf story was published last week, the resi[.]to Discord server vanished, Synthient’s website was hit with a DDoS attack, and the Kimwolf botmasters took to doxing Brundage via their botnet.

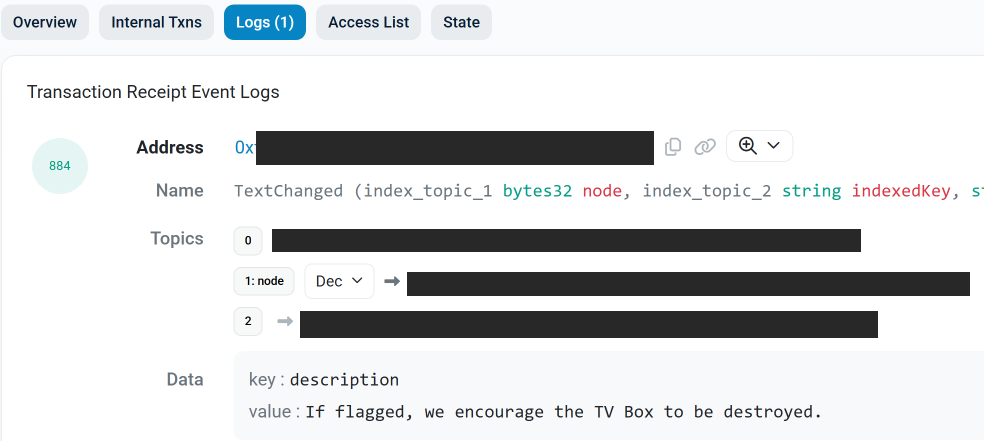

The harassing messages appeared as text records uploaded to the Ethereum Name Service (ENS), a distributed system for supporting smart contracts deployed on the Ethereum blockchain. As documented by XLab, in mid-December the Kimwolf operators upgraded their infrastructure and began using ENS to better withstand the near-constant takedown efforts targeting the botnet’s control servers.

An ENS record used by the Kimwolf operators taunts security firms trying to take down the botnet’s control servers. Image: XLab.

By telling infected systems to seek out the Kimwolf control servers via ENS, even if the servers that the botmasters use to control the botnet are taken down the attacker only needs to update the ENS text record to reflect the new Internet address of the control server, and the infected devices will immediately know where to look for further instructions.

“This channel itself relies on the decentralized nature of blockchain, unregulated by Ethereum or other blockchain operators, and cannot be blocked,” XLab wrote.

The text records included in Kimwolf’s ENS instructions can also feature short messages, such as those that carried Brundage’s personal information. Other ENS text records associated with Kimwolf offered some sage advice: “If flagged, we encourage the TV box to be destroyed.”

An ENS record tied to the Kimwolf botnet advises, “If flagged, we encourage the TV box to be destroyed.”

Both Synthient and XLabs say Kimwolf targets a vast number of Android TV streaming box models, all of which have zero security protections, and many of which ship with proxy malware built in. Generally speaking, if you can send a data packet to one of these devices you can also seize administrative control over it.

If you own a TV box that matches one of these model names and/or numbers, please just rip it out of your network. If you encounter one of these devices on the network of a family member or friend, send them a link to this story (or to our January 2 story on Kimwolf) and explain that it’s not worth the potential hassle and harm created by keeping them plugged in.

-

Fintech6 months ago

Fintech6 months agoRace to Instant Onboarding Accelerates as FDIC OKs Pre‑filled Forms | PYMNTS.com

-

Cyber Security7 months ago

Cyber Security7 months agoHackers Use GitHub Repositories to Host Amadey Malware and Data Stealers, Bypassing Filters

-

Fintech6 months ago

DAT to Acquire Convoy Platform to Expand Freight-Matching Network’s Capabilities | PYMNTS.com

-

Fintech5 months ago

Fintech5 months agoID.me Raises $340 Million to Expand Digital Identity Solutions | PYMNTS.com

-

Artificial Intelligence7 months ago

Artificial Intelligence7 months agoNothing Phone 3 review: flagship-ish

-

Artificial Intelligence7 months ago

Artificial Intelligence7 months agoThe best Android phones

-

Fintech3 months ago

Fintech3 months agoTracking the Convergence of Payments and Digital Identity | PYMNTS.com

-

Fintech7 months ago

Fintech7 months agoIntuit Adds Agentic AI to Its Enterprise Suite | PYMNTS.com